What is the Rotator Cuff?

The rotator cuff is a group of muscles which go from the scapula (wing bone) to the humeral head (ball of the shoulder bone). The front muscle is the subscapularis, the top muscle is the supraspinatus and the back two muscles combine, the infraspinatus and teres minor. Together these muscles work to keep the glenohumeral joint in place and initiate the movement of the arm above the head.

Over the top of the shoulder are larger muscles like the Deltoid, Pectoralis Major and Latissimus Dorsi. The small muscles work together to stabilize the glenohumeral joint and initiate the motion to allow the bigger muscles to help get your arm up over your head. These tendons help to rotate the arm within its socket which is where the name rotator cuff came from. If the small muscles don’t hold the glenohumeral joint in place the bigger muscles simply pull upwards which ‘shrugs’ the shoulder rather than raising the arm above shoulder height. In order for the arm to be raised up in the air all of these complex parts must each play a role. Weakness or damage to any element will cause problems when trying to use the arm. This is why rotator cuff injuries usually result in weakness, especially when trying to raise the arm overhead. The muscle that is most commonly injured is called the supraspinatus muscle and this is the one found between the acromion bone (roof of the shoulder) and humeral head (ball of the shoulder) where it can get pinched and damaged.

The terminology around rotator cuff tears can be quite confusing. Tears can be small or big but can also be partial or full thickness. They can be retracted and associated with muscle wasting, usually indicating a chronic tear. Since the rotator cuff is quite thick it is possible for only part of it to tear away from the bone. This can be a small or large (extensive) partial thickness tear and can also be on the top of the tendon (bursal sided partial thickness rotator cuff tear) or on the joint side (articular sided partial thickness rotator cuff tear). Unfortunately the articular sided tears usually do not heal on their own and often need surgical repair. Bursal sided tears often improve with the standard treatment for shoulder impingement. An extensive partial thickness tear can be more of a problem than a small full thickness tear.

A full thickness tear means that the whole thickness of the rotator cuff tendon has been pulled off the bone. These will almost always require surgery to fix them but if the tear is small enough and the patient’s activities very limited (such as an elderly patient) then non surgical management might be appropriate.

Tears tend to increase in size over time which is why we almost always recommend fixing tears in younger patients. If the tear progresses enough it will allow the ball of the shoulder to ride up against the acromion bone and create arthritis which is called a rotator cuff tear arthropathy. Younger people do get rotator cuff tears but they become more common as people age. This is probably because the interface between the tendon and the bone weakens and becomes more susceptible to injury with less capacity to heal. Many older patients will have rotator cuff tears if you get an MRI of their shoulder but unless they have symptoms they usually do not require treatment.

Large tears can ‘retract’ or pull backwards and scar down. This can make repairing them difficult or impossible so early referral and investigation (ideally within 6 weeks) is appropriate when a rotator cuff tear is suspected.

Symptoms

The symptoms from a rotator cuff tear and impingement can be very similar. In most cases people will recall a specific injury that led to the tear, compared to impingement which has a gradual increase in pain with activity. Common causes of rotator cuff tears include falling over, lifting something very heavy, getting pulled by a dog, rugby tackles or dislocating the shoulder if you are over 60 years of age. In some cases the tear is more degenerative with no history of a specific injury.

Some common symptoms of rotator cuff tears include:

- Arm and shoulder pain

- Weakness and tenderness in the shoulder

- Limited range of motion and pain, especially when raising and lowering your arm

- Snapping or cracking sensation when moving the shoulder

- Inability to rest or sleep on the affected shoulder due to pain

Clinical Examination

One of the most consistent findings when examining a patient with a rotator cuff tear is weakness of external rotation in adduction (weakness turning the arm outwards with your elbow in by your side). With a small tear there may not be much loss of motion but with a larger tear the person may not be able to raise their arm above their head.Imaging

Always start with a plain x ray. There are four important views. An AP in the plane of the scapula, a lateral, an axillary lateral a a supraspinatus outlet view. In most people these x rays will be normal but you might see signs of chronic repetitive injury to the rotator cuff such as sclerosis of the greater tuberosity of the humeral head, indicating that the rotator cuff is being pinched between the humeral head and the acromion bone. There also might be a hooked acromion with or without a spur digging into the rotator cuff. Other conditions such as calcific tendonitis and arthritis will show up on these x rays.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is almost useless when it comes to diagnosing a rotator cuff tear. It will miss a large number of tears and also report tears when they are not there. I believe my clinical examination more than I believe an ultrasound report of the shoulder.

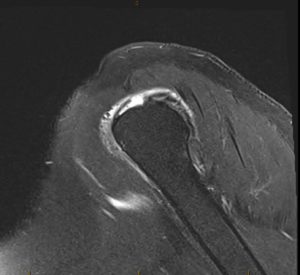

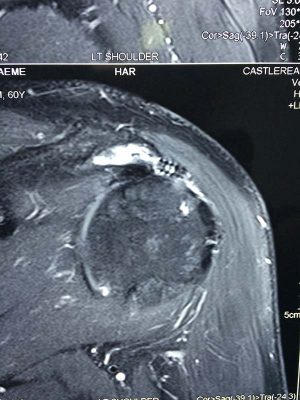

The gold standard test for rotator cuff tears is called a Gadolinium MRI Arthrogram. During this test a dye specific for the MRI scanner is injected into the shoulder joint. Without this dye many partial thickness tears of the rotator cuff will be missed. The gadolinium also helps show up any labral tears and capsular contraction (like a frozen shoulder). The MRI also looks at the degree of muscle wasting and amount of fatty infiltration giving some idea of the length of time the tear has been present. If the patient is unable to go into the MRI machine because they have a pacemaker or are claustrophobic the next best test is called a CT arthrogram which will show you the tears but not give any information about the quality of the muscle itself and whether there is any wasting, indicating a chronic injury.

How is a Rotator Cuff Injury Treated?

Treatment will depend on your symptoms, age, and general health. It will also depend on the size of the tear and how long it has been there. For older patients Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) combined with a physiotherapy home exercise programme is often enough. These people might need a subacromial corticosteroid injection from time to time to relieve pain and restore function. We know that these tears progress with time but for many lower demand older patients this is not a problem.

The most common treatment is surgical repair of the torn tendon back down to the bone. This is usually done using keyhole (arthroscopic surgery) techniques. Occasionally formal open surgery is still required but this is quite rare these days. If the tear cannot be repaired then other options such as a superior capsular reconstruction can be considered.

The operation is performed with a nerve block and general anaesthetic. Usually only one night in hospital is needed and you wake up in a sling. The sling is worn all the time (except for showers) for 6 weeks by most people. After six weeks a gentle physiotherapy range of motion exercise programme commences and gradually increases in intensity and strengthening over a 12 month period. People during any form of manual labour are generally off work for up to one year.

The success rate of the surgery is in the vicinity of 90%. The success rate and return of function is very dependent on the size of the tear (the bigger the tear the worse the result to some extent). Even with successful surgery you will never have a completely normal shoulder, but you should achieve good function and excellent pain relief. If you do not have surgery the tear does not heal and the tear will progressively increase in size with an associated increase in loss of function. If you then elect to have surgery at a later date that surgery is less likely to be successful and may not be possible at all if of the size of the tear has increased too much. People with a rotator cuff injury typically recover well with treatment. However, it’s common to injure the same shoulder again, especially if you do not change the way you use your shoulder. Elderly people are prone to rotator cuff problems and have a harder time recovering because their shoulders have a less robust blood supply.

Prevention

In many cases, a rotator cuff injury can be avoided with appropriate ergonomic adjustments to your activities. For example: To avoid reaching over your head repeatedly, use a stepping stool or ladder to reach higher objects. Avoid using your arms to push off from a chair and do not lift weights at or above shoulder height at the gym. Stay in the ‘safe zone’ which is below shoulder height and in front of the body. Exercises that strengthen the rotator cuff muscles also are an important part of prevention. Some of the rotator cuff muscles pull down on the upper arm bone as they work, widening the space that the tendons travel through.