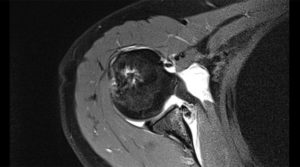

The shoulder is a round ball on a flat socket. This gives the joint great mobility and flexibility but it also means that in certain circumstances the ball can fall off the socket. The flat socket is deepened by a structure called the labrum which acts as a bumper to help keep the shoulder in joint. Thickenings of the joint lining capsule also tighten up to help keep the joint in position as the shoulder moves through various overhead positions. The muscles can only help to a very limited extent if the ball is about to fall off the socket (glenohumeral dislocation). At the time of acute shoulder injury many people think that they have dislocated their shoulder when they have, in fact, broken their collar bone (fractured clavicle) or separated their AC joint (Coracoclavicular ligament injury with acromioclavicular joint separation).

There are many descriptions of partial shoulder dislocations, with the ball of the upper arm coming just part way out of the socket. This is called a subluxation but is almost certainly actually a complete dislocation which is able to go back in by itself. A complete dislocation means the ball comes all the way out of the socket where it often gets stuck. The most common direction for the shoulder to dislocate is anteriorly (forwards) but posterior (backwards) and inferior (downwards) dislocations are possible too. Posterior dislocations are usually from seizures or electric shocks. There is very strong evidence that repeated episodes of subluxations or dislocations lead to an increased risk of developing arthritis in the joint. As few as 3 dislocations massively increases your risk of arthritis as an adult. If you are under the age of 18 when you have your first dislocation you are almost guaranteed to continue to dislocate your shoulder until it is operated on (surgical stabilisation).

First Time Dislocation

First time shoulder dislocations usually require a visit to the emergency department for an xray and to be put back into joint. As the tissues stretch out it becomes easier for the person to put the shoulder back in themselves. There is no evidence that wearing a regular sling for any length of time after the dislocation makes it less likely that the shoulder will dislocate again. In the “old days” we used to let people dislocate their shoulders several times before offering them surgery. We now know that dislocating the shoulder more than twice significantly increase the chance of developing arthritis later in life. The surgical techniques are much better, safer and more reliable than they were previously and now even first time dislocators are offered immediate stabilisation surgery.

Treatment

The basic principles of surgery for a shoulder dislocation are to repair the damaged structures and to tighten up the parts that have been stretched out. The most common way to achieve this these days is using keyhole techniques (arthroscopic stabilisation). It can also be done with an open capsular shift or with bone transfer operations (Laterjet procedure). The arthroscopic procedure achieves good results in cases where there have been fewer dislocations or if you are not going to return to “collision” sports. The arthroscopic operation has a success rate over 90%. The open operation has a higher success rate, especially in people who have had multiple dislocations, or who are very active and play high level contact sports. The success rate of the open operation is greater than 90% but it does require detaching and reattaching the subscapularis muscle to get into the shoulder. This operation is much more reliable for younger patients (under the age of 18) who have a might higher chance of re-dislocating their shoulder with a keyhole (arthroscopic stabilisation) procedure. The rehabilitation following both procedures is almost identical with 6 weeks in a sling and 6 months before return to sports is allowed.

Open Stabilisation

The incision (skin cut) is next to the skin crease in the armpit and can spread with time. There may be some permanent numbness around the scar, which is usually not noticeable. The operation involves cutting down to the shoulder joint and reattaching the torn labrum back to the bone with either stitches (that do not dissolve) or small screws or anchors which are sunk into the bone and do not require removal. The capsule (which has stretched out) is tightened using a double breasting procedure where a T-shaped split is made in the capsule and it is then tightened with one part being moved up and the other part down to reduce the overall volume of the capsule and stop the shoulder moving in abnormal directions. There may be some mild permanent stiffness but usually this is not very noticeable and does not cause any functional deficit. This operation does not deal with damage at the back of the shoulder and therefore is not suitable for posterior labral tears or instability.

Arthroscopic Stabilisation

The operation typically requires 4 cuts, 1 at the back, one at the side and 2 at the front of the shoulder. These are about 1cm long each. The labrum (or cartilage) which is torn off the bone is repaired with either a dissolving or plastic screw (we do not use metal these days) with a stitch attached to the end. It is not possible to tighten a stretched capsule as much with the arthroscopic technique as it is with the open stabilisation and this is one of the reasons that the redislocation rate is slightly higher with this technique.

What to do when the bones are damaged:

We know that if you only damage a small portion of the bone both the arthroscopic and open stabilisation operations will work well. If there is a large amount of bone loss then the bone needs to be replaced in order for the shoulder to remain stable. This is typically measured on a CT scan which will be organised in addition to an MRI scan if bone damage is suspected. Patients receiving this treatment typically have 20% or more bone loss from the glenoid. There are three ways that this procedure creates stability of the shoulder:

- The coracoid bone is cut off the from of the scapula and screwed onto the front of the glenoid. This transfer restores the glenoid surface eliminating any bony lesions that previously existed.

- The tendon transferred with the bone (Conjoined tendon) acts as a dynamic sling to reinforce the bottom half of the subscapularis muscle and also the (anteroinferior) joint capsule.

- The capsule is tightened and reattached to the glenoid. The operation is ideal for treatment of failed previous shoulder stabilisation, those with increased shoulder laxity (looseness) or if there is significant bone damage. Unfortunately it is being overused at the moment for treatment of collision athletes. Generally complications from this operation are more severe than the other operations (if they occur) and it may lead to problems in the future when we are dealing with the arthritis that will develop in these people.

It is not an operation that should be done if an arthroscopic or open stabilisation will work just as well for that particular patient. Return to sport is about 2 months faster because it relies on bone healing rather than soft tissue healing. The potential for complications from this operation is higher than the other two operations.

Recovery

After shoulder stabilisation surgery you will not be able to return to any sports for 6 months (4 months for a Laterjet procedure). Doing so would compromise the result of the surgery.

When you do return to contact sports you will need to use a brace for the first season for all training sessions and all games. This is to protect the repair. The brace is usually fitted by the team physiotherapist. All patients who return to doing weights should permanently avoid training in positions that can stretch the shoulder, such as shoulder press and full extension in bench-press.

FAQs

If you are young when you first dislocate your shoulder you are very likely to dislocate it again. This is particularly true if you return to collision sports. Each time you dislocate your shoulder you do more damage and we know that the more times you dislocate your shoulder, the more likely you are to get arthritis later in life. If it for this reason that we offer surgery to almost all patients who have dislocated their shoulders.

The recovery from these two operations is exactly the same.

You will be in hospital for one night only. You go home with waterproof dressing on which allow you to shower but you stay in the sling daytime and nightime (except for showers) for six weeks.

Physiotherapy starts 6 weeks after the operation and continues until 6 months after surgery when you are ready to return to sport. The physiotherapist is a teacher so you learn exercises which you then do at home. There is very little ‘hands on’ treatment required.

A Laterjet procedure should only be done if there is significant bone loss present. It is an operation which has a potentially high complication rate but works very well if bone is missing from the glenoid. If there is no bone loss then an open stabilisation with a capsular shift is the operation of choice for contact athletes.